Individuals

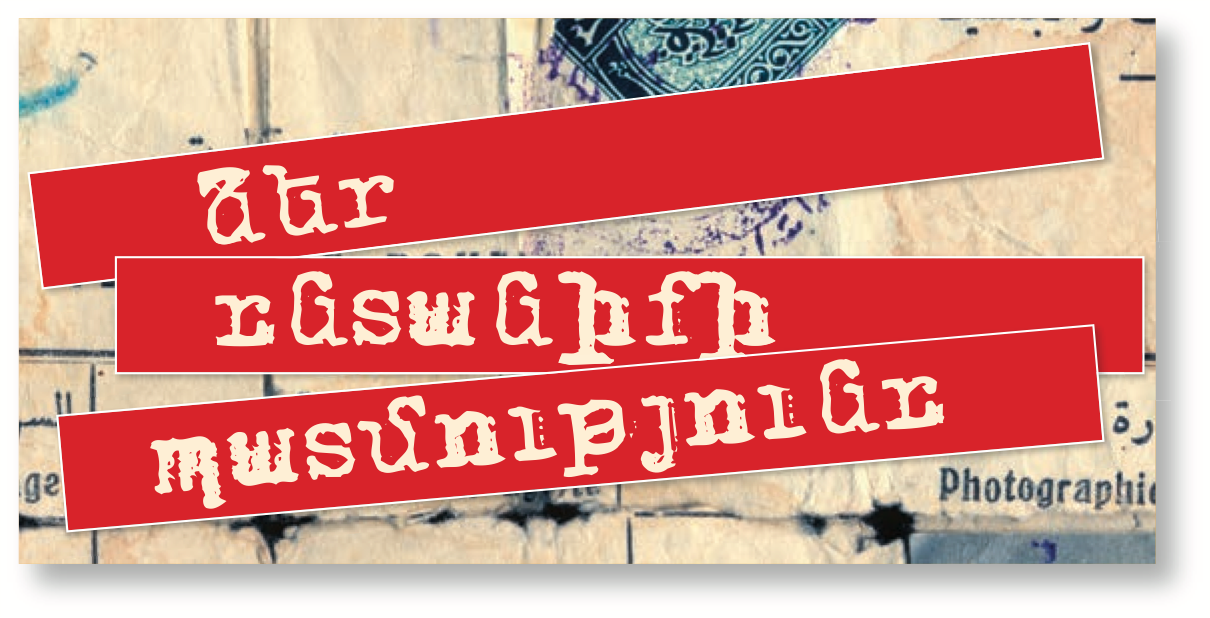

THE HOMELAND ALSO PUNISHES

Persecution, in the eyes of local residents, was a normal occurrence. After the sovietization of Armenia, thousands of Armenians fell victim to jailings, deportations and executions. Such things were unexpected and inexplicable to the repatriates, Armenia’s new citizens. They believed that by coming to Armenia they would find the safest of places to live. But it quickly became apparent that news of their past “crimes and transgressions” arrived in Armenia with them or often even before.

Between 1946 and 1952, more than 800 repatriates were subject to persecution. The charges levied against them were primarily:

- Collaboration with the secret services of European countries or the USA

- Having served in the armies of European countries (notably England and France)

- Anti-Soviet propaganda and actions

- Membership in the Armenian Revolutionary Federation and the other bourgeois-nationalist parties (when convenient, the Social-Democrat Hnchak and Ramgavar-Liberal parties were also classified as such, even though they backed repatriation)

Charges were often founded on assumptions, perceptions, and on information provided by local or foreign so-called ‘sources’, and were described as treason to the fatherland.

Repatriates at the center of attention of state security agencies were mainly “exposed” due to speaking their mind freely and openly. Just expressing dissatisfaction regarding the situation in the country or to compare Soviet reality to the life one had in their former country was reason enough for the guardians of the regime to take swift action.

As we know from the diaries and oral testimony of those repatriates who were persecuted, it was first suggested that they cooperate with state security agencies and provide information regarding the ideas, attitudes and complaints expressed in their circles (primarily amongst repatriates). By agreeing to such a proposal, the repatriate could avoid punishment, even though in certain cases it failed to do so. When repatriates refused, they were not only charged with complaining and for speaking up, but for much more serious crimes noted above in generalized form.

Sifting through the cases of the victims of repression, one may think that they were prepared legally. However, from the investigations conducted after the death of Stalin we often see that the evidence hadn’t been sufficiently studied, that the information provided by the ‘sources’ hadn’t been properly examined, that extenuating circumstances weren’t take into account, etc. Given this contradiction, it becomes clear that confessions resulted from physical and psychological pressure, and witness testimony due to an environment of fear.

Those so charged were tried by the Supreme Court of Soviet Armenia, the Military Tribunal, or the Special Consultative Body of the Soviet Armenia’s Ministry of State Security.